Reading note: How Buildings Learn

Notes on how some buildings come to be loved

Quick takeaways

- If you’re building a home for the first time, this book is invaluable. After reading it, you will understand the structural and design decisions which result in buildings that come to be loved for a very long time. You will also learn how to avoid the most common building mistakes.

- Buy the book on Amazon

What makes some buildings come to be loved?

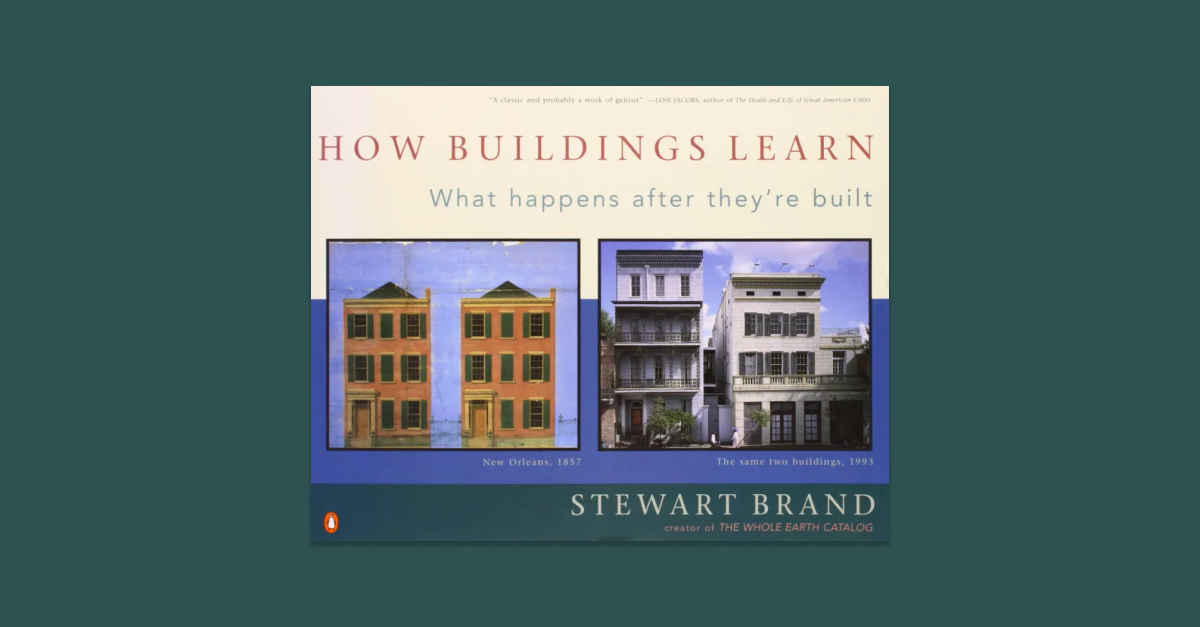

This is the central question that Stewart Brand answers throughout How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built.

I’m glad I read A Pattern Language before How Buildings Learn, because the latter made frequent references to the former, and I enjoyed recognising the references. (I don’t mean to imply that reading one is critical to understanding the other. You can definitely jump first into How Buildings Learn.)

I came away with a better understanding of how different design decisions would impact how well our home would mature over time.

What makes some buildings come to be loved?

Brand argues convincingly that age plus adaptivity is how a building comes to be loved.

Everywhere he looked, he saw again and again that the most loved buildings, regardless of whether they were commercial, residential, sacred or otherwise, were the ones that:

- were easy to repurpose, and adapted gracefully to changing needs

- were long-lived, or were built in a way that allowed them to last for a long time

These might seem like pretty obvious observations, but choosing to build with age and adaptivity in mind has numerous implications for how you approach a building project, from the choices you make about the building’s foundations, to the material you choose for its outer walls, to the angle at which you slope the roof.

Again, it sounds obvious, but look around and you quickly realize how little we design for our buildings to evolve and age gracefully.

Almost no buildings adapt well. They’re designed not to adapt; also budgeted and financed not to, constructed not to, administered not to, maintained not to, regulated and taxed not to, even remodeled not to. But all buildings (except monuments) adapt anyway, however poorly, because the usages in and around them are changing constantly.

“All buildings are predictions,” Brand says and he explains how, as certain as morning, buildings almost always outgrow their original functions as needs, family sizes, budgets, technology and society itself evolves and changes. So despite our best efforts, buildings will change, and the most loved buildings are the ones that are set up to do this with grace.

Robert Campbell wrote … “Recyclings embody a paradox. They work best when the new use doesn’t fit the old container too neatly. The slight misfit between old and new—the incongruity of eating your dinner in a brokerage hall—gives such places their special edge and drama…. The best buildings are not those that are cut, like a tailored suit, to fit only one set of functions, but rather those that are strong enough to retain their character as they accommodate different functions over time.”

Over the course of the book, Brand patiently walks you through the material decisions builders have made over time, and more critically, the results of those decisions. He writes in a very engaging, conversational style, and the effect is like receiving an oral history of good building decisions through time from your favourite uncle.

What are some things that make buildings last longer, and more adaptable?

One of the best things about the book is how seriously it attempts to catalog the specific decisions that result in long-lived buildings. Brand approaches this task with both an anthropologist’s sense of curiosity, and a contractor’s keen eye for detail.

I asked Ridout what the historic building inventories and archaeology of Maryland suggested about the comparative survivability of the various kinds of old buildings. He said the main survivors were masonry buildings, even though they were only 15 percent of what was originally built. Medium to large houses survived the best, because there is always use for them. Small houses were built shoddy and disposable. Barns survived fairly well, thanks to being solidly constructed. Specialized farm buildings perished of obsolescence, with one interesting exception.

“Small domestic outbuildings that are well built tend to survive. Everybody can find a use for a 12- or 14-foot-square building. Meat houses, for example, tended to be very well built. They were either of masonry, log, or very heavy timber frame construction, partly because they were carrying a lot of weight—maybe 2,000 pounds of ham hanging from the roof—and they had to be theft proof. They usually were relatively close to the main house, so they’re still convenient to this day. These days they’re full of lawnmowers and weedcutters and turpentine and bicycles. They’re very hard to measure because they’re always crammed with junk.”

I’m not going to be able to list every single quality that Brand says aid adaptability, but here are a handful that stood out to me.

Pay special attention to how materials connect to each other, and their replacement cycles

In his blog post titled Reality has a surprising amount of detail John Salvatier marvels at how even the smallest physical activity hides a surprising amount of complexity.

I found myself thinking about Salvatier’s post a lot while reading this book, because there are several places where Brand shows how a seemingly minor design or construction detail results in major consequences over time.

For example, take the question of which material to use for your roof cladding:

The 100-year-plus materials [for roofing] are lead, tile, slate, and metal. When lead finally corrodes after a century or so, it needs to be completely replaced. Tile and slate are heavy, expensive, and sometimes breakable, but they are fireproof and beautiful, and they will last the life of most buildings (often much longer, since they can be recycled). New concrete tiles are not as attractive as traditional clay tiles—a 12,000-year-old technology—but they cost less. Slates are soulful. However, they don’t hold up in sunny climates quite as well as tile (ultraviolet rots them), they need steeper pitches to reduce moisture damage…

Metal roofs have become tremendously popular since architects began getting sued for leaks. The best of all is standing-seam terne-coated stainless steel or copper. It is light, nonflammable, moderately priced, good looking, nearly maintenance-free, and waterproof (it also sheds snow, branches, and prowlers). In The Low-Maintenance House, Gene Logsdon reports, “Every roofer I ask says that metal roofs today are the best buy for the money of any kind of roofing.” Len Lewandowski concludes in Preventive Maintenance of Buildings, “The standing seam roof offers the lightest weight, lowest maintenance, and most cost-effective roofing solution available today.”

And there’s even more fine detail about how to hold the material in place:

Slates … require stainless steel or copper nails if you want the fasteners to last as long as the slates.

Survivors of hurricanes in the American southeast say that metal roofs should be fastened with screws rather than nails—stainless steel of course.

The point is, even a decision as seemingly small as what types of nails to use can have longterm consequences, and after reading this book, you’ll begin to think obsessively about joints, and how materials physically connect to each other.

Consider the matter of how to hold brick walls together.

Recent brick walls, however, may be shorter-lived than their ancestors. Since the early 1960s, most brick walls have been built with a cavity of some 2 inches between an outer layer of decorative brick and the inner layer of cheaper brick or concrete block. (The visual giveaway is that the exterior wall is usually all “stretcher bond”—you see only the long side of the bricks since none are extending inward to form a bond with inner bricks.) The short-term advantages are many—notably higher strength for lower cost and better protection against wind-driven rain. Any water that gets through the permeable bricks of the outer layer will encounter the “rainscreen” protection of the cavity and drip down to the bottom of the cavity, there to return to the outside via weep holes.

Now here comes the disturbing part:

The vulnerable component of this system is the metal ties that reach across the cavity to hold the two layers together. When they corrode, the walls become much weaker, with no visible indication that there is any problem until parts of the outer layer fall off or the entire wall collapses. Inspection requires hiring professionals, and correction with new ties is horrendously expensive. Having started with cavity walls in the late 19th century, Britain has more experience with the problem than the US. According to an alarming little book, Cavity Wall Tie Failure, in the some 12 million cavity-wall brick buildings in England, tie failure will be found in 70 percent of the buildings from the 1800s, 35 percent in the walls built from 1920 to 1950, and a shocking 40 percent in the ones from 1950 to 1981.

Now, you might be thinking to yourself: “I don’t have time to think about all of this. This is what I pay architects and contractors for!”

And you’re right!

But Brand recommends that we still ask probing questions of our building teams. Ask how long different materials will last before they will need to be replaced. If you care about longevity and adaptability, these questions might spark a discussion with your building team about the compromises they’re making, and what impact - if any - those tradeoffs will have on the longevity of the building.

Avoid flat roofs

Flat roofs leak. It turns out that this is apparently a huge issue with contemporary buildings, and in several parts of the book Brand attempts to warn the reader away from overly clever design moves that inevitably result in an expensive building with a roof that leaks.

“Flat roofs always leak,” said an estates manager interviewed by the researchers for The Occupier’s View. The researchers observed that even those few occupiers (22 percent of the sample) “who had expressed a preference for modern glass boxes seemed to be resigned to the fact that part of the price of a modern building with a flat roof was the likelihood (or virtual certainty) of roof leaks.” The overwhelming majority of the occupants of the fifty-eight modern business buildings—78 percent of them—said that after their experience they would prefer to be in a building with “traditional pitched tile roof and brick construction.”

How Buildings Learn was written in 1994, but it appears that the issue of leaky roofs in contemporary buildings is still with us. A recent dramatic example from September 2020 shows the new Renzo Piano-designed Paris Courthouse, leaking rainwater from the 19th to the 6th floor. In the tweet, the poster complains that this never happened in the former building, the ancient Palais de Justice.

#Viedavocate Megafuite au nouveau palais de Justice de Paris, du 19eme étage au 6eme, cela coule coule coule. Dans le palais historique une telle catastrophe n'est jamais arrivée. C'est bien la peine de faire du neuf ! pic.twitter.com/prddAXBVj2

— Caroline Mecary (@carolinemecary) September 16, 2020

When it comes to reliably keeping rain out, it appears that nothing beats the tried and tested pitched roof in all its many flavours - hip roofs, gable roofs, and so on.

Avoid designing around the latest technology

One of the big mistakes Brand identifies from speaking to experts is the well-meaning desire to build around the latest technology. The problem is that technology reliably changes so quickly that by the time the building is done, the tech might have changed, or become obsolete. The MIT Media Lab building offers a cautionary tale.

Boston architect William Rawn notes that professors are notorious for wanting space designed precisely around their current research, and never mind the future. The Media Lab is burdened with a number of expensive overspecified spaces, such as a pair of rooms designed for wall-size rear-projection—research that was no longer even going on when the building opened. The rooms defaulted to poor storage space, then even poorer office space. A long, narrow theater was built and wired especially for advanced interactive movie research. All it’s used for is lectures, and its design makes it one of the worst lecture spaces on campus.

When it comes to tech, Brand cautions:

The temptation to customize a building around a new technology is always enormous, and it is nearly always unnecessary. Technology is relatively lightweight and flexible—more so every decade. Let the technology adapt to the building rather than vice versa, and then you’re not pushed around when the next technology comes along.

Overinvest in high quality materials and craftsmanship

“Build with high quality materials” is one of those recommendations that goes in through one ear and out the other. We collectively badly underestimate how taking shortcuts here results in compounding losses over time.

For example, almost everyone builds in concrete in Ghana, despite the ample quantities of clay deposits with which to make brick, an incredible building material. Brick is basically fireproof, is a better thermal regulator, is stronger than concrete, repels termites, and ages beautifully.

Brick is a superlative building material, the product of 8,000 years of experience in firing clay into modular units that can be mortared together and stacked by hand into unreinforced structures as high as sixteen stories. It is completely fireproof. London had no more Great Fires after rebuilding in brick in the 1670s, and commercial building owners in the 1990s still favor brick because they more than make up for its extra expense with saved insurance costs. As of 1989, brick was the most popular of all exterior cladding materials in the US for nonresidential construction—31 percent of the market. Maintenance is minimal. All brick walls need is to be repointed (the outer 3/4 inch of the mortar joints replaced) every sixty to one hundred years.

And quality craftsmanship, while costly in the short term, more than pays for itself if future cost savings.

Quality builders are expensive too, but the investment pays well later in terms of durability and flexibility. Fine artisans treat code requirements as setting a minimum standard rather than a maximum. They know that step dimensions in stairs have to be consistent to within three-sixteenths of an inch or people will stumble and get hurt. (A major source of architectural malpractice suits is for sloppy or overly creative stairs.)

Good artisans also know or can figure out the details that will make a building work right for the inhabitants, so the toilet-paper dispenser can be easily reached and the shower doesn’t spray the bathroom floor or burn the hand that adjusts the hot water. Well-made buildings are fractal—equally intelligent at every level of detail.

Both high quality material and craftsmanship results is an adaptable building that retains its value for generations, versus the norm of buildings that fall apart within 30 years.

90 degree walls are the most adaptable

Another one of those obvious things that it’s easy to forget when you’re in the euphoria of drawing. Simple 90 degree walls are infinitely more adaptable

As for shape: be square. The only configuration of space that grows well and subdivides well and is really efficient to use is the rectangle. Architects groan with boredom at the thought, but that’s tough. If you start boxy and simple, outside and in, then you can let complications develop with time, responsive to use. Prematurely convoluted surfaces are expensive to build, a nuisance to maintain, and hard to change.

Beauty, at every scale of detail

The most important idea in How Buildings Learn is that age plus adaptability is how buildings come to be loved.

But my favourite idea in the book is this: “Well-made buildings are fractal—equally intelligent at every level of detail.”

It is the idea that beautiful buildings are beautiful at every scale: they’re beautiful in elevation, in plan, in section. From cornice to door knob, there is evidence of a loving attention to detail.

California architect Julia Morgan was trained at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. All of her buildings have the fractal quality of offering delight at every scale. This building in San Francisco, called The Heritage (1925), shows the same degree of complexity as the tree next to it. The brick detailing and terra cotta trim on the west-facing facade change with the sun all afternoon The bay windows mark the public rooms within. Of this home for the elderly, Morgan’s biographer writes, “The enthusiasm of the residents and long waiting list testifies to a carefully conceived and executed environment for the aged that has rarely been equalled.”

I see this quality of fractal beauty often in Studio Contra’s approach.

In every line, you see the influence of a mind and a heart at work. It speaks of a level of care that made my mother whisper that it’s as if they designed the home for their own family. It has made the entire project even more meaningful to me.

Who will enjoy this book?

If you’re looking to build something that not only endures, but thrives over the next 100+ years, you will enjoy this book immensely.

I intend our home to be important to our family for a very, very long time, so I found the insights invaluable.

The writing style is also really engaging. Brand did his homework, speaking to what seems like many hundreds of people, and he lets their voice come through, so How Buildings Learn does not read like a dusty textbook. It feels more like being in the room with lots of really smart domain experts.

If you’re a more visual person, you might prefer to watch the BBC TV documentary based on the book. Brand co-wrote and presented the series, and he’s uploaded all 3 hours of the 6 part series for free viewing on YouTube.

Episode 1 of 6 - Flow

Episode 2 of 6 - The Low Road

Episode 3 of 6 - Built for Change

Episode 4 of 6 - Unreal Estate

Episode 5 of 6 - The Romance of Maintenance

Episode 6 of 6 - Shearing Layers

Finally, if your architects and contractors favour a contemporary style, this book will be useful for catching potential usability issues early and asking informed questions.

Who will not enjoy this book?

Fair warning: if you’re an architect, this book might be painful reading.

Brand blames contemporary architects for many of the ills of the modern built environment, and he takes every opportunity he can to take them to task.

Brand on how contemporary architects don’t know how to keep the rain out:

Does the building manage to keep the rain out? That’s a core issue seldom mentioned in the magazines but incessantly mentioned by building users, usually through clenched teeth. They can’t believe it when their expensive new building, perhaps by a famous architect, crafted with up-to-the-minute high-tech materials, leaks. The flat roof leaks, the parapets leak, the Modernist right angle between roof and wall leaks, the numerous service penetrations through the roof leak; the wall itself, made of a single layer of snazzy new material and without benefit of roof overhang, leaks. In the 1980s, 80 percent of the ever-growing postconstruction claims against architects were for leaks.

Brand on architecture education:

Adaptive use is the destiny of most buildings, but the subject is not taught in architectural schools. Any kind of remodeling skills are avoided in the schools because they seem so unheroic, and the prospect of remodeling or rehabilitation happening later to one’s new building is even more taboo. Predictably paralyzed buildings are the result. But suppose preservationists taught some of the design courses for architects, developers, and planners. The subject would not be how to make new buildings look like old ones. It would be: how to design new buildings that will endear themselves to preservationists sixty years from now. Take all that a century of sophisticated building preservation has learned about materials, space-planning, scale, mutability, adaptivity, functional tradition, functional originality, and sheer flash, and apply it to new construction.

Overall, Brand is extremely frustrated by what he sees as contemporary architects being so distracted by things that don’t matter, that they’ve forgotten the fundamentals.

Building maintenance has little status with architects. They see the people who do the maintaining as blue-collar illiterates and the process of upkeep as trivial, not a part of design concerns. As a result of this attitude, Pompidou Centre (1979) in Paris, the spectacular inside-out arts complex designed by Sir Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano supposedly to accommodate all manner of change, cannot accommodate what the weather does to all that exposed piping. The place became an exorbitant scandal of rust and peeling paint. But even ordinary office buildings suffer from the lapse. According to The Occupier’s View, the survey of fifty-eight new business buildings near London, “a staggering one-fifth of the sample said that the need to clean their windows had not even been considered during the design and construction of the building.” Also lighting fixtures in the grand lobbies were unreachable for lamp replacement, and internal drains from the flat roofs had no access hatches for inspection and cleaning.

Conclusion

For most of us, a house is one of the single biggest investments we will ever make. How Buildings Learn invites us to learn how to do it right, and to create something that grows and learns with us.

We are convinced by things that show internal complexity, that show the traces of an interesting evolution. Those signs tell us that we might be rewarded if we accord it our trust. An important aspect of design is the degree to which the object involves you in its own completion. Some work invites you into itself by not offering a finished, glossy, one-reading-only surface. This is what makes old buildings interesting to me. I think that humans have a taste for things that not only show that they have been through a process of evolution, but which also show they are still a part of one. They are not dead yet.

I am very glad I read this book while we were in the design stage of the house, and I recommend it wholeheartedly. You can buy How Buildings Learn on Amazon.

(If you enjoy my writing and want to support my personal research projects, the best way is to buy me a book!)

-

Family Home

-

Family Home

-

Family Home