Reading note: A Pattern Language

Notes on the canonical guide to designing “buildings which are poems”

Quick takeaways

- This book is a must-read if you’re a first-time home builder. It will give you a clear way to think about how to design your home, and give you the vocabulary you need to have constructive conversations with your architects. You will be able to make confident design decisions you won’t regret.

- It contains 253 recommendations for building well-loved places. Each of these recommendations is called a pattern and comes with detailed commentary, as well as numerous reference photos and drawings.

- Buy the book on Amazon

In early 2020, I began working with my architects (the great team at Studio Contra) on the design of a home for my family.

I had never done anything like this before, so as part of my preparation for the project, I read various books related to architecture design and criticism. A Pattern Language was the very first book I read, and it provided a foundation that helped me think clearly about important decisions throughout the design process.

We had already begun designing by the time I started reading A Pattern Language. I had already shared a design brief with the architects which included a list of the major spaces the house should contain, short profiles of the members of the family who would be stakeholders, design references with detailed notes, and the development control guidelines. Studio Contra had already shared an initial floor plan and early massing models, which I loved.

What are development control guidelines? The site for my home is a serviced plot purchased from a development company, and the development control guidelines is a document that explains all the the rules that builders must adhere to, such as setbacks and the maximum number of stories.

But as the date of the second design review approached, I found myself less confident about some of the decisions I had already made, and would make in the next few weeks. Were we making the most efficient use of space? Is there an ideal ceiling height for bedrooms? What should the walls be made of? I knew Studio Contra would have excellent recommendations, but the extent of my ignorance really bothered me.

While I had encountered A Pattern Language several times in the past, I only made the active decision to read it after stumbling across this reading note on Blas Moros’ website. That proved to be one of the best decisions I made in 2020.

An introduction to A Pattern Language

Written over the course of 8 years and published in 1977, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction remains one of the most popular and best-selling books on architecture design. It was written by Chistopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein, with writing credits to Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King, and Shlomo Angel.

The book’s central argument is that if you look around the best-loved places across cultures, you will notice a number of repeating ideas, and that building according to these principles sets on you on the path to creating places that people really enjoy.

The book then shares 253 examples of these principles, which they name patterns.

The elements of this language are entities called patterns. Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.

The authors believe that many of thee patterns are universal, appealing to all members of the human family regardless of time, culture, or geography.

Many of the patterns here are archetypal—so deep, so deeply rooted in the nature of things, that it seems likely that they will be a part of human nature, and human action, as much in five hundred years, as they are today.

While one must always take claims of universality with a grain of salt, I personally found myself quietly shouting “YES” at several points while reading this book. It has a way of articulating certain things about buildings you’ve always liked or disliked, but never had the words to describe.

Each pattern is presented in more or less the same template.

Every pattern has a name and a number, and some patterns have a number of asterisks. The book uses asterisks next to the pattern name to signal how strongly they believe that this is a universal pattern. Two asterisks means that they’re very certain. One asterisk means that they believe they’ve identified a universal pattern, but suspect that it could be improved upon. And no asterisk means that they are fairly certain that this is not a universal pattern.

Next, there will be a brief sentence summarising the central argument of the commentary. Following this will be several words of the commentary. Some are very short (only a few paragraphs) while some go on for several pages.

And then finally, the commentary will conclude with a direct recommendation about what to do. This section is almost always prefaced with the word “Therefore”

How to use this book when designing a house

Feel free to jump around to patterns that catch your eye

A Pattern Language is not laid out like a typical non-fiction book. I would recommend reading the “Using this book” section at the beginning, but after that, you should feel free to approach it more like textbook, or an encyclopaedia.

By which I mean, you don’t need to read it linearly from beginning to end. There are several patterns, for example, that are only relevant to someone building on the scale of a city, which won’t be super relevant to you if you’re building a single home your yourself.

Feel free to jump around, pausing when you see a pattern that seems highly relevant to your situation, and paying very special attention when you see patterns with asterisks.

Consider the authors’ level of certainty in each pattern

Like I shared previously, the pattern titles include a notation that signals the authors’ level of confidence in the pattern’s core claim.

The solutions we have given to these problems vary in significance. Some are more true, more profound, more certain, than others. To show this clearly we have marked every pattern, in the text itself, with two asterisks, or one asterisk, or no asterisks.

In the patterns marked with two asterisks, we believe that we have succeeded in stating a true invariant: in short, that the solution we have stated summarizes a property common to all possible ways of solving the stated problem. In these two-asterisk cases we believe, in short, that it is not possible to solve the stated problem properly, without shaping the environment in one way or another according to the pattern that we have given—and that, in these cases, the pattern describes a deep and inescapable property of a well-formed environment.

In the patterns marked with one asterisk, we believe that we have made some progress towards identifying such an invariant: but that with careful work it will certainly be possible to improve on the solution. In these cases, we believe it would be wise for you to treat the pattern with a certain amount of disrespect—and that you seek out variants of the solution which we have given, since there are almost certainly possible ranges of solutions which are not covered by what we have written. Finally, in the patterns without an asterisk, we are certain that we have not succeeded in defining a true invariant—that, on the contrary, there are certainly ways of solving the problem different from the one which we have given. In these cases we have still stated a solution, in order to be concrete—to provide the reader with at least one way of solving the problem—but the task of finding the true invariant, the true property which lies at the heart of all possible solutions to this problem, remains undone.

Pay very special attention to patterns with two asterisks.

Make notes of the patterns that call out to you

A Pattern Language is a reference book, meant to be returned to again and again, but it’s also a very dense book. I would strongly recommend taking detailed notes about the patterns that you have a strong reaction to, so you can quickly revisit them in future.

Discover architectural elements you hadn’t considered before

The scope of our imagination during any design process is partly defined by our lived experience, and if you only rely on architectural elements who’ve personally seen before, you might miss out on beautiful experiences such as window seats, alcoves, or roof gardens. Happily, A Pattern Language is an encyclopaedia of architectural elements. Don’t be afraid to approach it as a buffet of ideas, and then pick and choose the ones that make sense for your project.

Use patterns as a guide during design reviews to catch potential issues

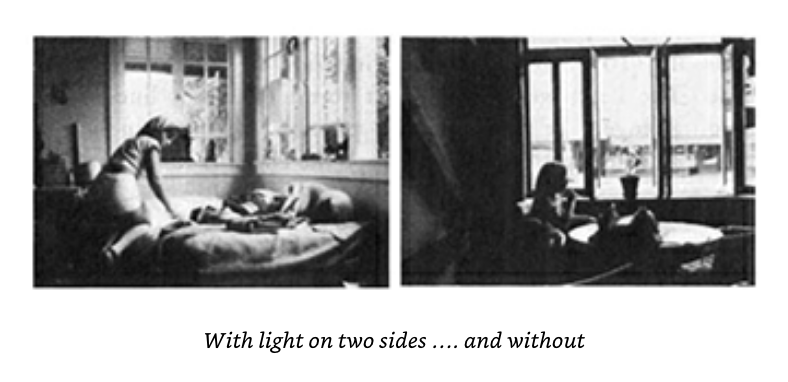

Let me use an exaggerated example: say you’re reviewing drawing plans and you notice that none of the bedrooms have windows. Since this goes against 159 LIGHT ON TWO SIDES OF EVERY ROOM**, it could spark a discussion with your architect to understand their thinking.

Layer and overlap patterns together to create something beautiful

The authors go to great lengths to explain that successful buildings are like a tapestry that weave the patterns together to create something that’s greater than the sum of its parts.

It is possible to make buildings by stringing together patterns, in a rather loose way. A building made like this, is an assembly of patterns. It is not dense. It is not profound. But it is also possible to put patterns together in such a way that many many patterns overlap in the same physical space: the building is very dense; it has many meanings captured in a small space; and through this density, it becomes profound.

If each architectural element is a note of music, find ways to create a composition that ties multiple notes together, to make “buildings which are poems.”

The compression of patterns into a single space, is not a poetic and exotic thing, kept for special buildings which are works of art. It is the most ordinary economy of space. It is quite possible that all the patterns for a house might, in some form be present, and overlapping, in a simple one-room cabin. The patterns do not need to be strung out, and kept separate. Every building, every room, every garden is better, when all the patterns which it needs are compressed as far as it is possible for them to be. The building will be cheaper; and the meanings in it will be denser.

It is essential then, once you have learned to use the language, that you pay attention to the possibility of compressing the many patterns which you put together, in the smallest possible space. You may think of this process of compressing patterns, as a way to make the cheapest possible building which has the necessary patterns in it. It is, also, the only way of using a pattern language to make buildings which are poems.

Some of my favourite patterns

117 SHELTERING ROOF**

For reasons I don’t fully understand, the roof of the building is the element that caused me the most anxious concern.

Until we began on the project I had never been actively conscious about the fact that some roofs are pitched and some are flat. A very early version of the design included a tucked roof, a contemporary move where eaves of the building didn’t overhang, but were designed such that the walls of the building rose higher than the eaves.

I tried hard to like it, but reading A Pattern Language gave me the vocabulary to explain to myself and to the architects why it rubbed me the wrong way. I remember the visceral sense of relief from reading this section and thinking “Okay, I’m not crazy.”

The roof plays a primal role in our lives. The most primitive buildings are nothing but a roof. If the roof is hidden, if its presence cannot be felt around the building, or if it cannot be used, then people will lack a fundamental sense of shelter.

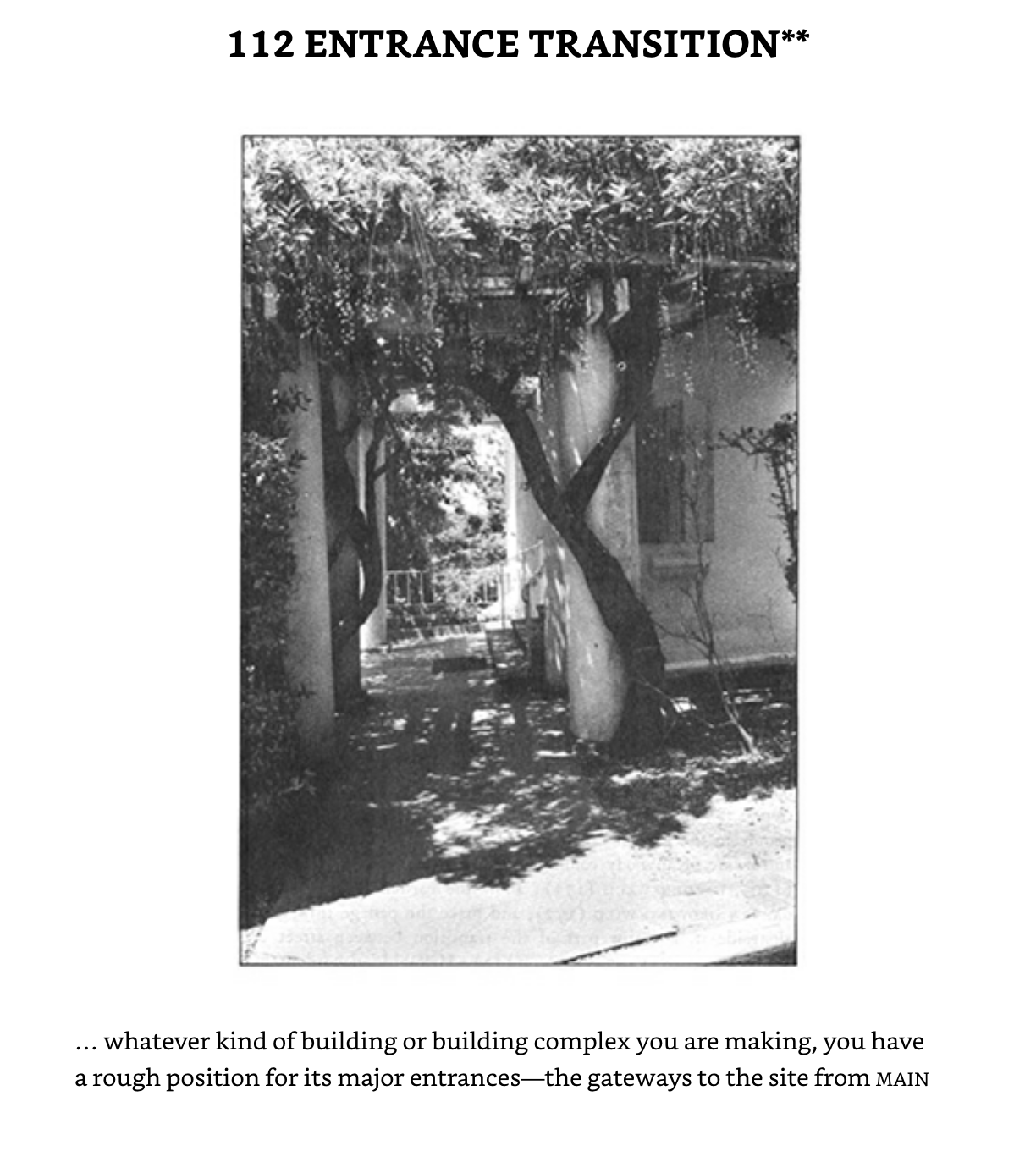

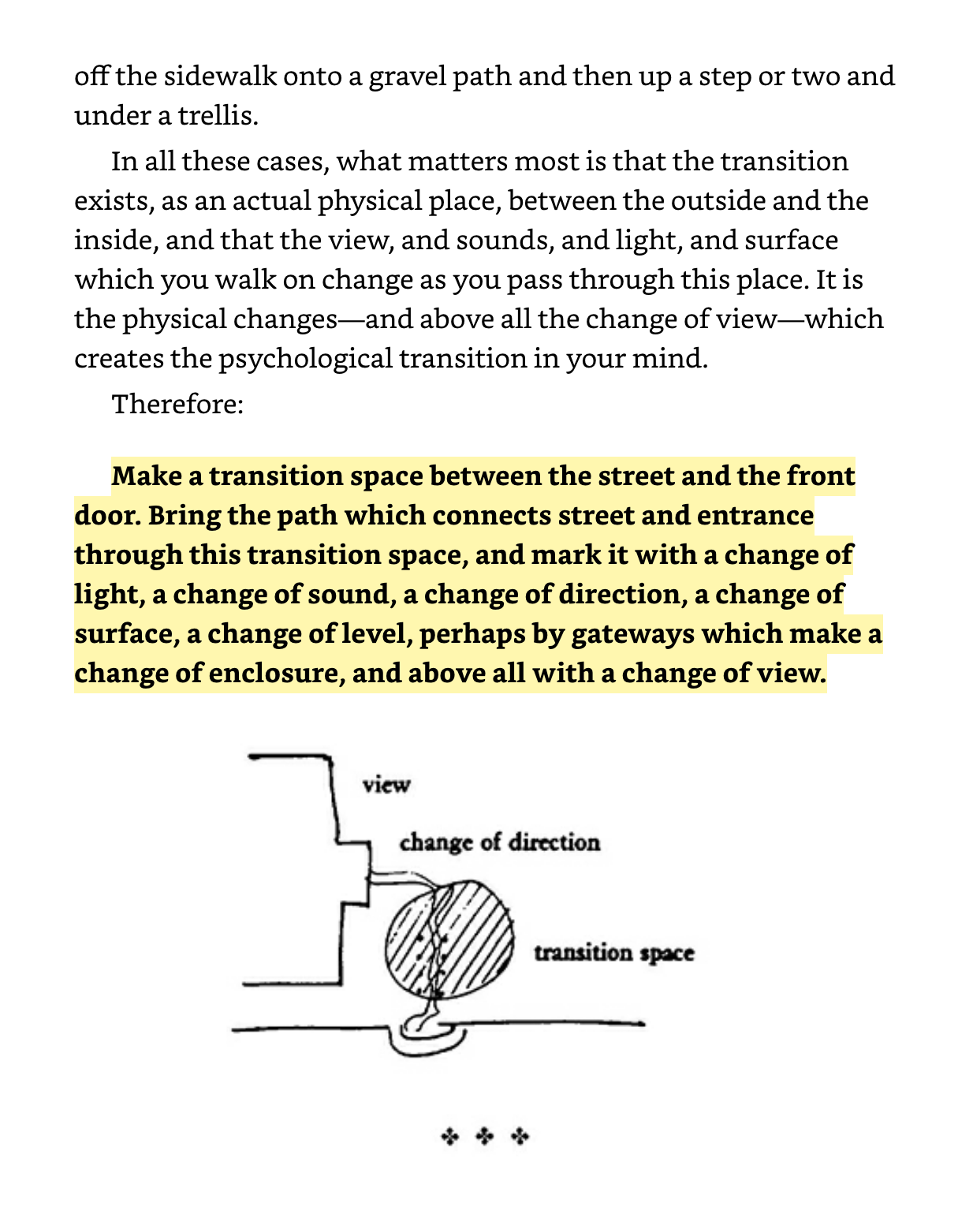

112 ENTRANCE TRANSITION**

This is one of those thing that you know intuitively, but it’s surprisingly easy to forget this when you’re creating static floor plans, and attempting to maximize the build area.

Buildings, and especially houses, with a graceful transition between the street and the inside, are more tranquil than those which open directly off the street. The experience of entering a building influences the way you feel inside the building. If the transition is too abrupt there is no feeling of arrival, and the inside of the building fails to be an inner sanctum.

The transition must, in effect, destroy the momentum of the closedness, tension and “distance” which are appropriate to street behavior, before people can relax completely.

This would explain why people are often unwilling to go without a front lawn, even though they do not “use it.”

127 INTIMACY GRADIENT**

This is another example of something we all know intuitively, but reading the “why” was valuable. Also, during a later design review, I realised that Studio Contra had already choreographed the spaces along this principle. The book helped me further appreciate their work.

Unless the spaces in a building are arranged in a sequence which corresponds to their degrees of privateness, the visits made by strangers, friends, guests, clients, family, will always be a little awkward.

In a building which has its rooms so interlaced that there is no clearly defined gradient of intimacy, it is not possible to choose the spot for any particular encounter so carefully; and it is therefore impossible to give the encounter this dimension of added meaning by the choice of space. This homogeneity of space, where every room has a similar degree of intimacy, rubs out all possible subtlety of social interaction in the building.

Lay out the spaces of a building so that they create a sequence which begins with the entrance and the most public parts of the building, then leads into the slightly more private areas, and finally to the most private domains.

159 LIGHT ON TWO SIDES OF EVERY ROOM**

This one blew my mind. I thought back to all of my favourite rooms, and how every single one honoured this principle. I don’t think I realized how much light I require in a room until I read this (I have literally moved cities in order to have closer access to a room that makes me light-drunk). Pattern 159 is probably my single favourite pattern in the book.

When they have a choice, people will always gravitate to those rooms which have light on two sides, and leave the rooms which are lit only from one side unused and empty…

This pattern, perhaps more than any other single pattern, determines the success or failure of a room. The arrangement of daylight in a room, and the presence of windows on two sides, is fundamental. If you build a room with light on one side only, you can be almost certain that you are wasting your money. People will stay out of that room if they can possibly avoid it. Of course, if all the rooms are lit from one side only, people will have to use them. But we can be fairly sure that they are subtly uncomfortable there, always wishing they weren’t there, wanting to leave—just because we are so sure of what people do when they do have the choice.

135 TAPESTRY OF LIGHT AND DARK*

Still in line with revelations about light, I love this pattern in the way it disrupted my easy understanding of light. I used to think more light was uniformly better, and this pattern introduced me to the idea that it’s just as important to have dark areas.

In a building with uniform light level, there are few “places” which function as effective settings for human events. This happens because, to a large extent, the places which make effective settings are defined by light.

People are by nature phototropic—they move toward light, and, when stationary, they orient themselves toward the light. As a result the much loved and much used places in buildings, where the most things happen, are places like window seats, verandas, fireside corners, trellised arbors; all of them defined by nonuniformities in light, and all of them allowing the people who are in them to orient themselves toward the light.

We may say that these places become the settings for the human events that occur in the building … and since light places can only be defined by contrast with darker ones, this suggests that the interior parts of buildings where people spend much time should contain a great deal of alternating light and dark. The building needs to be a tapestry of light and dark.

Barbara Erwin explores this idea in a lot more detail in her book Creating Sensory Spaces: The Architecture of the Invisible.

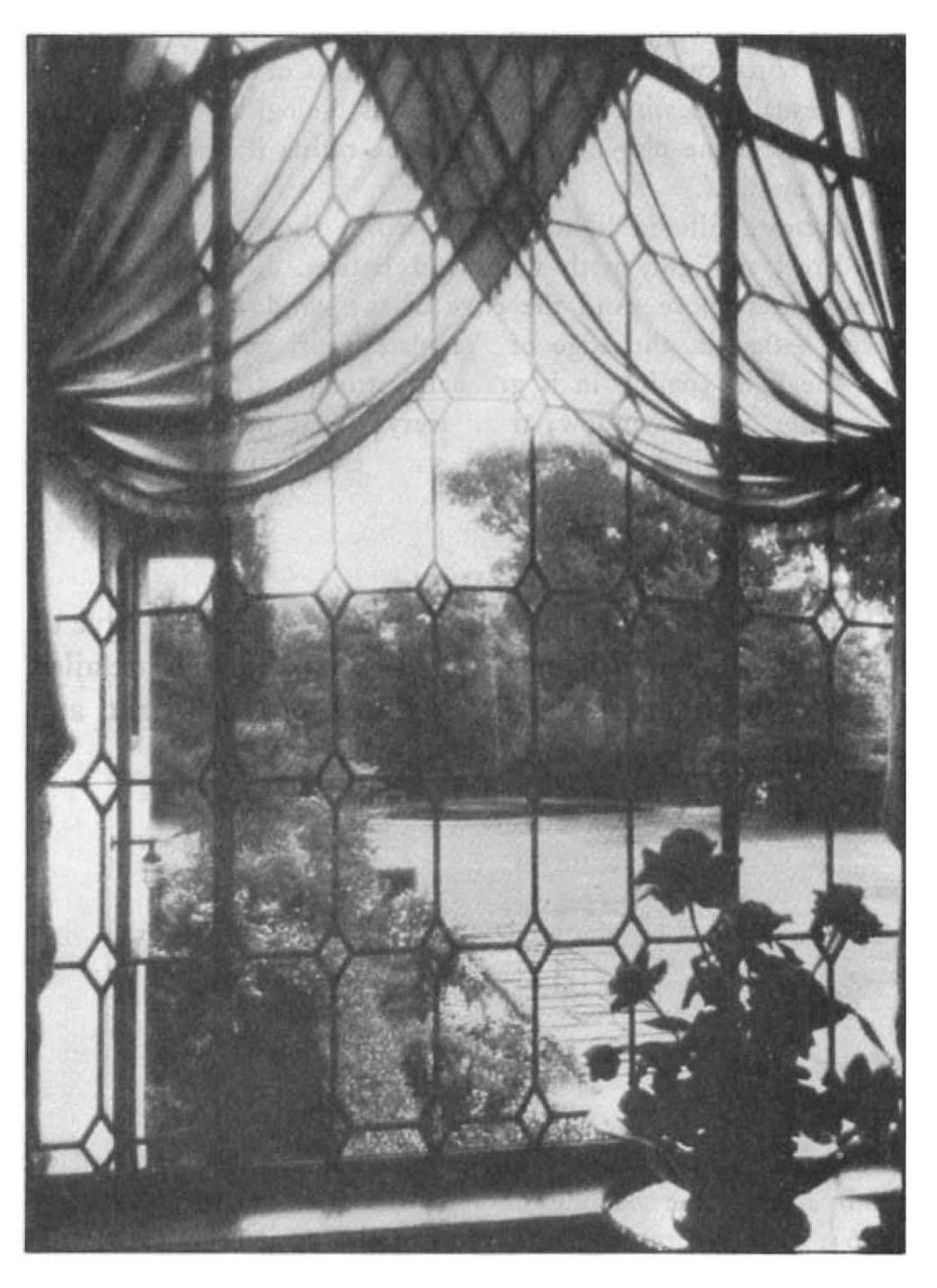

239 SMALL PANES**

My obsession with light is matched only by my obsession with windows, and this pattern was a revelation. It explained to me why I react so strongly and negatively to sheer plate glass windows.

When plate glass windows became possible, people thought that they would put us more directly in touch with nature. In fact, they do the opposite. They alienate us from the view. The smaller the windows are, and the smaller the panes are, the more intensely windows help connect us with what is on the other side.

Thomas Markus, who has studied windows extensively, has arrived at the same conclusion: windows which are broken up make for more interesting views. (“The Function of Windows—A Reappraisal,” Building Science, Vol. 2, 1967, pp. 101–4). He points out that small and narrow windows afford different views from different positions in the room, while the view tends to be the same through large windows or horizontal ones.

Another argument for small panes: Modern architecture and building have deliberately tried to make windows less like windows and more as though there was nothing between you and the outdoors. Yet this entirely contradicts the nature of windows. It is the function of windows to offer a view and provide a relationship to the outside, true. But this does not mean that they should not at the same time, like the walls and roof, give you a sense of protection and shelter from the outside. It is uncomfortable to feel that there is nothing between you and the outside, when in fact you are inside a building. It is the nature of windows to give you a relationship to the outside and at the same time give a sense of enclosure.

Later, I will share specific examples of how we applied ideas from A Pattern Language into the design of the house.

Who will enjoy this book?

You will love A Pattern Language if you’re building a home for the first time, and you’re feeling nervous about everything you don’t know.

While it contains several big ideas, this book is written with a lot of heart and grace, and in a very simple and accessible way. It will give you the vocabulary you need to be able to have constructive conversations with your architects, and it will help you make confident design decisions you won’t regret.

I also think architects, contractors, city planners and other professionals would also enjoy this book for how it explains why certain design moves feel so much more satisfying than others. If you’ve ever found yourself knowing in your gut that something was the better move, but lacked evidence to support it, this book will likely give you an arsenal of supporting evidence and references.

Who will not enjoy this book?

I suspect that people who exclusively enjoy a stark modernist / contemporary approach to architecture will be very annoyed by this book.

The authors have numerous unkind things to say about contemporary architecture and are openly hostile in several places. For example, one of the most impassioned sections of the book is a jeremiad against very tall buildings (see 21 FOUR-STORY LIMIT **, which begins “There is abundant evidence to show that high buildings make people crazy.”)

I believe that it’s possible to design a building in a contemporary style that still meets the principles of A Pattern Language, but don’t be surprised if your architect frowns when you mention you’ve read the book, because the authors target contemporary architects specifically for some harsh criticism.

Conclusion

Reading A Pattern Language set me up perfectly for the rest of the design stage of the project, and I love the design that came out of following its principles. I was also very pleasantly surprised to find that many of the other helpful books I read later made frequent reference to this canonical text.

If you’re working on a building project, I could not recommend this book more strongly. It will give you the principles, language, and confidence to create a beautiful, human-scale home.

You can by A Pattern Language on Amazon.

(If you enjoy my writing and want to support my personal research projects, the best way is to buy me a book!)

-

Family Home

-

Family Home

-

Family Home