Favourite cookbooks of 2020

The four titles that deepened my understanding of what cookbooks could be

I don’t really cook much.

I also own exactly zero (physical) cookbooks.

And yet, I habour a minor obsession with cookbooks, and began keeping a running list of favourites in 2020.

I have three theories for why I find cookbooks so compelling.

Part of it, for sure, is that I have a disturbingly intense love of food and all the toe-curling things it does in my mouth.

In 2013, I did an internship in Mexico City, and on my first day of work my colleagues treated me to lunch. The restaurant served bread rolls to keep us occupied while they prepared the main meals. Seven years later, I still remember this moment very vividly: the restaurant had done something with the bread where the outside was crisp while the inside was sinfully soft. So as you bite into these soft mounds, your teeth break the skin of the glaze, and sink into the pillowy soft, sweet “meaty” inside. The rolls were also coated with some kind of salt, so that every hit of sweetness had a salty counterpoint. Every bite was a revelation.

This is a flavour of my relationship with food. Food is a full body experience for me 😅

I also started to look at food differently after a conversation a few years ago with Chef Selassie Atadika, founder of Midunu. She explained how food is undertheorized in our part of the world, and how food and cooking are deeply political - quite literally at the intersection of culture, technology, religion, and economics.

For example, as the Sahara Desert continues creeping southwards, governments on the West African coast should really be looking into the cultural engineering necessary to wean our populations off our current food staples, and towards hardier grains which don’t require as much water. This type of forward-thinking planning is why Chef Atadika is experimenting with fonio (This Guardian article does a good job od introducing fonio, and the Wikipedia entry is also instructive.)

Finally, and most randomly, I’ve had an idea at the back of my mind for a while for a fantasy novel with a food-based magic system. To explain what I’m going on about, here is the earliest public mention I can find on the idea, reproduced below to make it easier to read.

Random: one day I want to flesh out a fantasy universe with a magic system based entirely around food and cooking. eg. Special yeast that’s alive in more ways than one. Special salts made from dragons’ tears. Teas you can only make from leaves that bloom on the site of a murder. Stimulants that help you think in a higher order of maths.

There’s something comical about the idea of a battlefield ringed by giant cauldrons, belching hallucinatory vapours to confuse enemies. Also something evocative about the idea of grimoires as giant, bound cookbooks you can only read after ingesting certain tinctures.

And then there’s the question of what the gender and class dynamics would be in such a world. What happens when every plate, pot, and saucepan is a literal battlefield? Would love to read stories from a place like this.

In this magic system, cookbooks would be, of course, grimoires.

Anyway, due to some combination of these reasons (and others, I’m sure) I pay attention to interesting cookbooks.

Here are the four cookbooks that caught my eye in 2020.

The French Laundry, Per Se

I discovered Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry, Per Se via a series of tweets by Andy Matuschak.

I’m very embarrassed to say this, but until I saw this tweet about The French Laundry, Per Se and its accompanying photo, I legitimately had NO IDEA that cookbooks come with ESSAYS!

As usual, the best part is the essays, which unpack tacit knowledge from eminent practitioners. pic.twitter.com/eHmz6mJkPW

— Andy Matuschak (@andy_matuschak) October 29, 2020

I purchased a digital copy of The French Laundry, Per Se on the back of Andy’s recommendation and I’m still reeling what I found inside.

Forget every assumption you have about what cookbooks are: in addition to a wealth of recipes, The French Laundry, Per Se is a goldmine of insightful essays on talent development, supply chain management, formal and informal cultures of learning, and several meditations on the creative process.

Again, read this book if you nurture a creative practice as an artist, architect, designer, writer, or software developer, or if your practice involves taking care of people, like in medicine, teaching, policing, or the performing arts.

It doesn’t matter if you have no interest whatsoever in cooking the recipes. The essays touch on so many things relevant to creators, and you will come away from this book enriched with a deeper appreciation for the special magic that audience and performer create together.

And then, of course, there is the food.

My God.

You must understand: I have literally no exposure to professional cooking. It’s very possible that these things are common knowledge, but there were several times while reading this book where I simply gaped at the lengths to which they would go to achieve a flavour outcome.

In this book, you learn that frost causes a chemical reaction that increases the sugar content in cauliflower, so they harvest the cauliflower heads at a specific time to achieve this specific flavour.

One chilly winter morning, our gardener came into the kitchen, thinking his cauliflower had been destroyed by an unexpected frost. But when David tasted it, he found that it was almost sweet. He loved it. Our gardener later figured out that the sudden cold had sent a signal to the cauliflower that made its carbohydrates spike—thus the term “frost-kissed.”

That very day, it was served as a salad that included black truffle and hazelnuts to Michael Bauer, former restaurant critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. The cauliflower’s natural sweetness worked beautifully. Today we serve it as a bavarois, or light mousse, for a canapé. We glaze it with a barely set gelée made from unripened green oranges picked from a tree in our neighborhood.

The green orange has a pleasantly sour flavor that marries well with the garden sorrel and crispy puffed cauliflower. The bavarois is a lot like the cauliflower panna cotta I originally served as a companion to the Oysters and Pearls in the early days of The French Laundry.

You learn that smoking meat over different kinds of fruit wood produces different kinds of flavour.

We tie the venison crosswise for the most compact shape and even cooking and serve it with a sauce made from Paradigm Winery grapes that have been dried on the vine and intensely flavored. Paradigm, our neighbor just a couple of miles up the road from The French Laundry, is run by a Napa family whose roots here go back more than a century. We love that we’re able to smoke the meat over grape knots, gnarled pieces of grapevine pruned by the winery. They’re great to smoke with, as are grape leaves. Of course, charcoal is fine, too, if that’s what you have.

Our “everything” mix combines chopped fried garlic and shallot and sunflower, poppy, sesame, and caraway seeds. We buy sturgeon whole, skin and bone them, then smoke them over applewood. After the fish has cooled, it’s simply paddled with about a third as much softened cream cheese and some butter, and finished with minced shallot and Agrumato lemon oil.

So exacting are the restaurant group’s standards that they will go to extreme lengths to get the quality of ingredients they desire.

For example, they own several acres of gardens which an army of gardeners tends to, 8 to 20 hours a day, to serve their restaurants with fresh produce.

The French Laundry has a three-acre garden directly across the street from our restaurant. It is a great source of pride for all of us, and a pleasure for visitors to Yountville and our neighbors here. And for our chefs, the garden is the ultimate luxury.

We also have a small garden behind Ad Hoc, a half mile from The French Laundry, an acre at the nearby Trefethen vineyards, and a one-acre stone fruit orchard in Napa. And four beehives—three for honey (about thirty pounds per hive per year) and one just for the bees, kept in the hollow stump of a sycamore tree that had been in front of my dad’s house next to the restaurant.

We grow a thousand varieties of plants; 250 of them supply food to the restaurants, including over 1,400 pounds of tomatoes alone each season. Our garden chefs grow plants to be eaten, to be drunk, to be admired for their beauty and fragrance alone. They grow passion fruit vines in the parking lot; jasmine, violas, pansies, and lilies for infusions; and fresh herbs for distillations. And I’ve revived the honeysuckle in front of the restaurant that was so prominent when Don and Sally Schmitt owned The French Laundry.

At least twice, the restaurant group has started completely different businesses to meet their supply needs.

All our restaurants combined order about 32 kilograms of caviar a week—nearly 3,500 pounds each year. That’s a lot of caviar. So we’ve partnered with Shaoching Bishop, a businesswoman with a passion for caviar, in our venture Regiis Ova, or “Royal Egg.” Shaoching has been able to source farmed caviar of extraordinary quality. And so caviar remains one of the great luxuries of life.

Perhaps the biggest change in our stocks came in 2019, when we started TKMM Stock Co. in Portland, Oregon, to make our veal stock. It now arrives in 2-liter cryovaced pouches, and former employees who return are astonished when we open one for them and it smells exactly like The French Laundry of 1996, with the scent of Veal #1 and Veal #2 reducing in the screened-in porch.

We started the company out of practical concerns. We simply had to make so much stock each week that it prevented our cooks from accomplishing what they needed to, in terms of both space and time. And those giant, unwieldy stockpots could result in dangerous spills. All this was solved with a stock of the same—or even better—quality.

If in doubt about the restaurant group’s maniacal focus on control, you learn that they will go as far as designing new plates for their food.

In our redefined bread service, François makes an individual roll of great delicacy and aesthetic beauty, usually a lamination of two different-colored doughs, with a delicate exterior and a soft crumb. Each guest receives one roll, along with Diane’s butter. (This also gave us an opportunity to design a new plate for this course.)

And so on.

The craft. The precision. The striving. The absurd lengths.

It’s overwhelming.

It’s exhausting in a painfully delicious way.

While I already had a healthy respect for chefs going into this book, I came out on the other end in complete awe. More, I came away feeling like I had permission to dare more greatly in my own craft.

I have barely scratched the surface of this remarkable book. I intend to distill its lessons carefully over the next many months.

You can get The French Laundry, Per Se from Amazon.

Dishoom: From Bombay with Love

I’ll get to talking about this book in a moment, but first, please allow me to gush for several paragraphs about Dishoom, the restaurant.

I discovered Dishoom by way of this excellent profile by Dan Fromer in The New Consumer, and I’ve been obsessed with them ever since.

The restaurant group pays homage to the Irani cafés set up by Persian immigrants in India in the late 19th century / early 20th century, and each of their eight locations is a love letter to the food of Bombay.

I love that they create a new story for every location. As they plan a new location, they imagine it as a real Irani café infused with Bombay history, then they write a founding myth as a short story which guides how they design the space. You can read the founding myths of all 8 restaurants here.

To enter a Dishoom restaurant is to step through a portal and into a pocket universe, and the brand very intentionally uses copy and design to create this sense of entering a different world, even going so far as to create these gorgeous coins - a fictive currency that serves as their version of a gift card.

This is what Dishoom co-founder Shamil Thakrar said in The New Consumer piece.

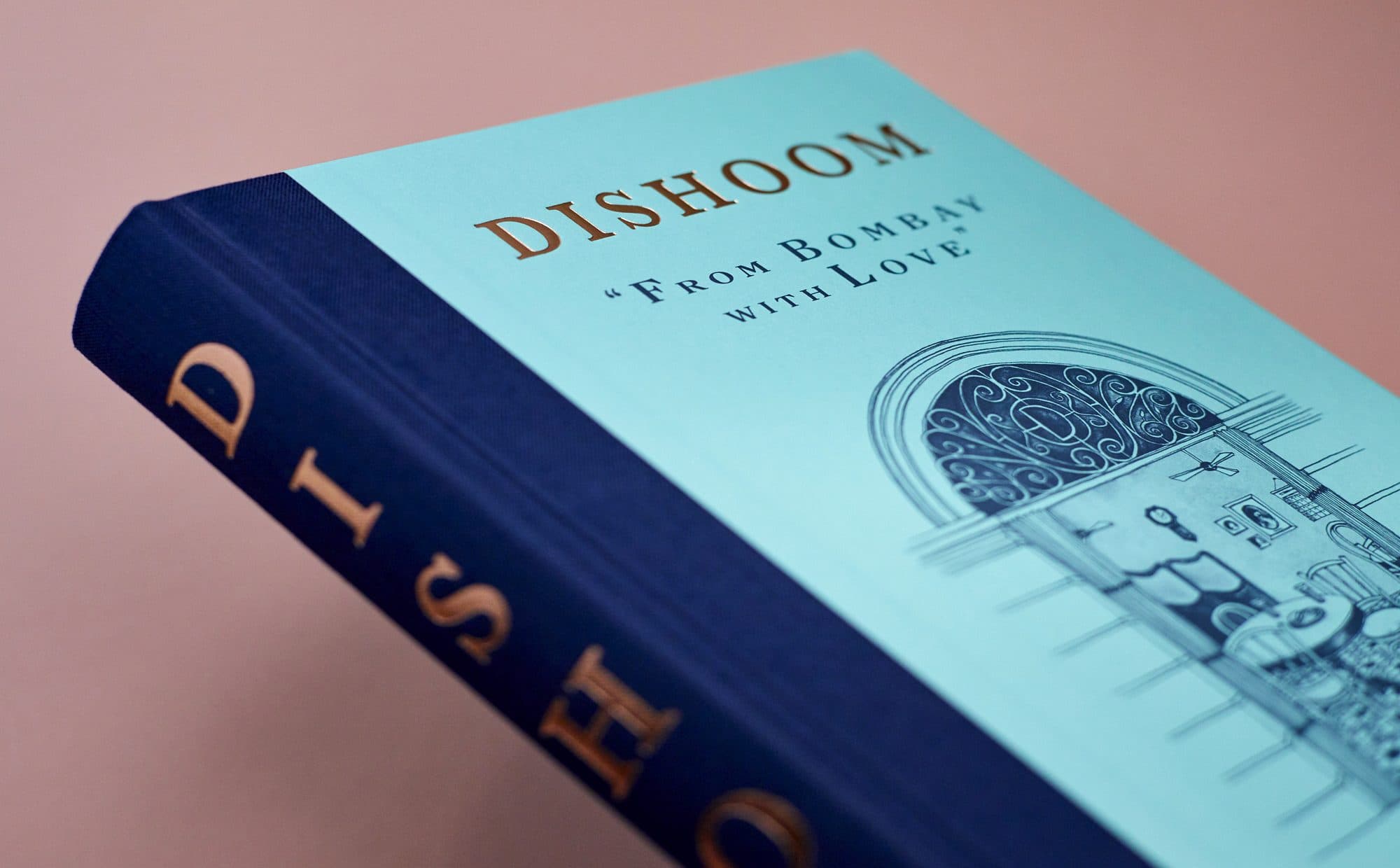

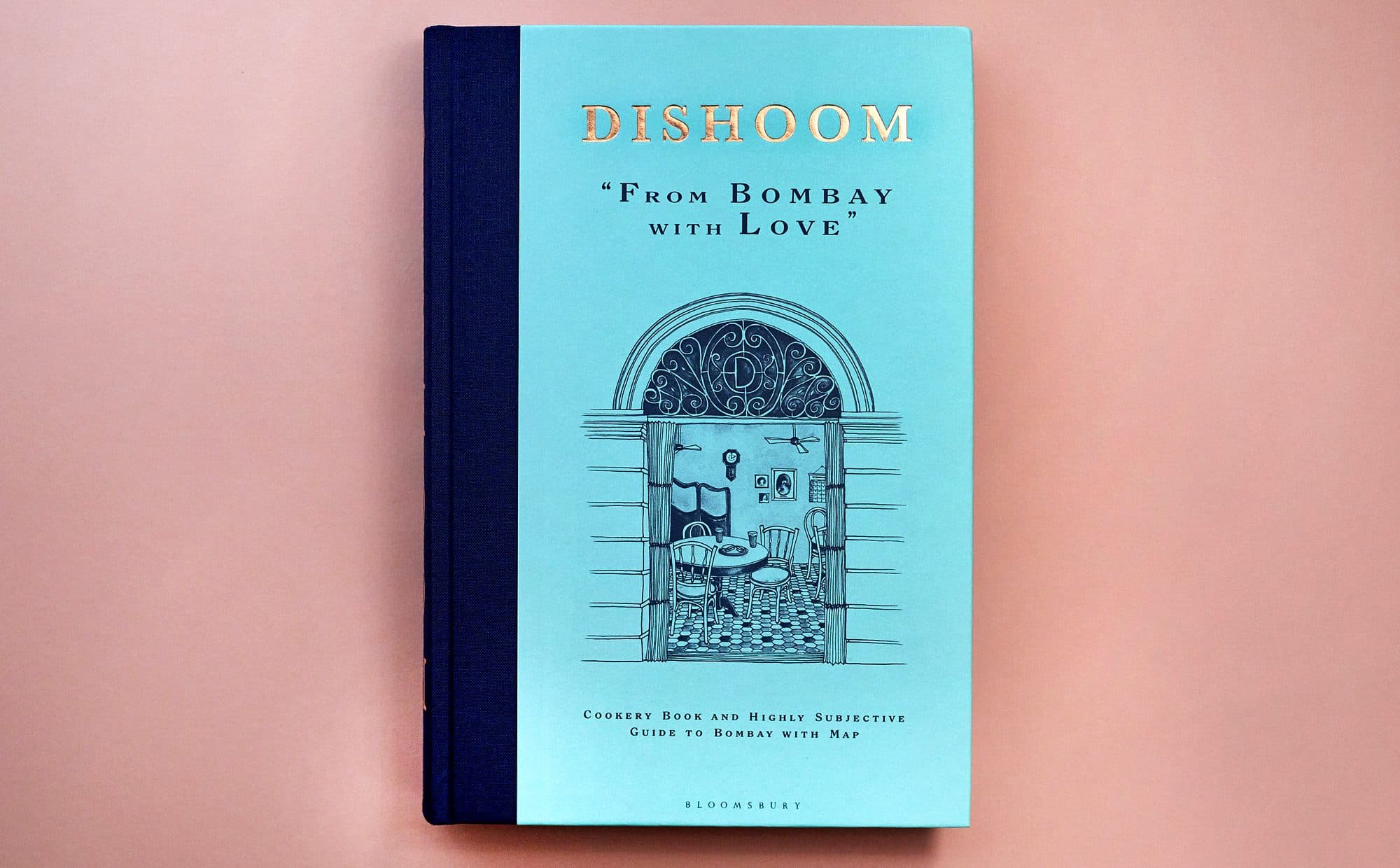

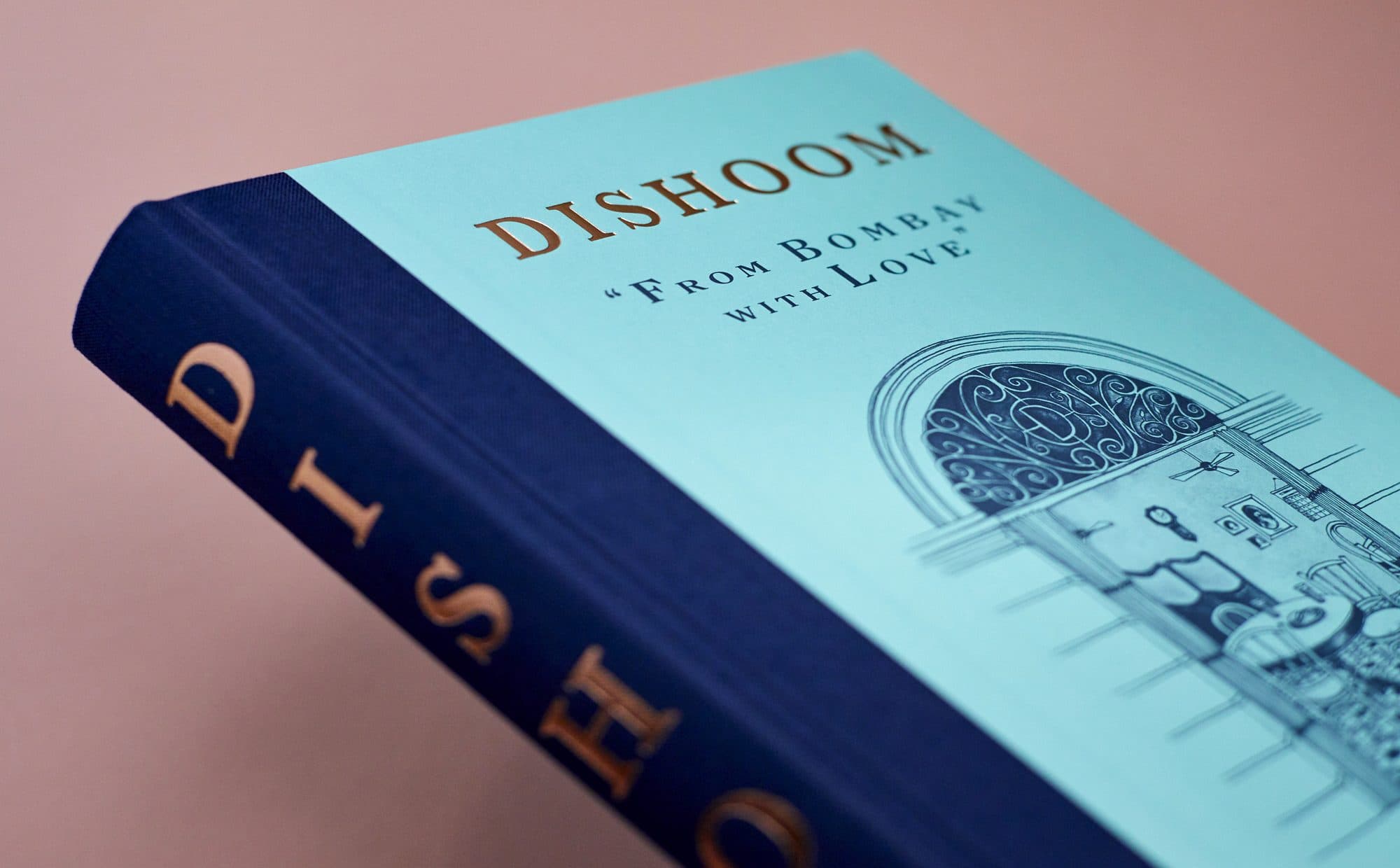

We’ll only take a site which allows us to create our world. We think about Dishoom as an entry into a different time and place. Even if you look at the cover of our book, we’re thinking about you coming through this door into our world. You’ll see it’s a [cookbook], but also a “highly subjective guide to Bombay” with a map.

I love Dishoom’s distinct brand voice. Where most brand copy aspires to inoffensive sameness, every single piece of writing I’ve read from Dishoom has a certain searing clarity. The writing crackles with intelligence and old-souled earnestness. I remember reading their goodbye message when they shut down during the first COVID-19 surge in March 2020, and just marvelling at the quality of communication.

In the past few days and weeks, coronavirus has blown our world apart. Last week already feels like a year ago, the present is unrecognisable, and the future is extremely uncertain…

We are still struggling to understand a world with no restaurants in it. The industry that we’ve proudly been a part of for the past decade will likely be permanently changed. Most of our friends and neighbours have already closed, and we hope and pray that they will make it to the other side of this severe storm.

We’ll be there too, on the other side, welcoming you back with very big smiles, pots of chai and enormous warmth.

I believe that almost all the copy is written by co-founder Shamil Thakrar? Probably the most rich example of his work in action is his annual letters at the end of the year. His 2020 letter is powerful, and worth a read.

And I love, love, love their cookery book, Dishoom: From Bombay with Love. (They are very particular about calling it a “cookery book” versus a “cookbook.” I have no idea why, but I love it.)

To clarify, I haven’t actually read this book yet (I usually read digital first, but this is one I feel like I should only read physically) but just knowing that that his object exists has seized my imagination.

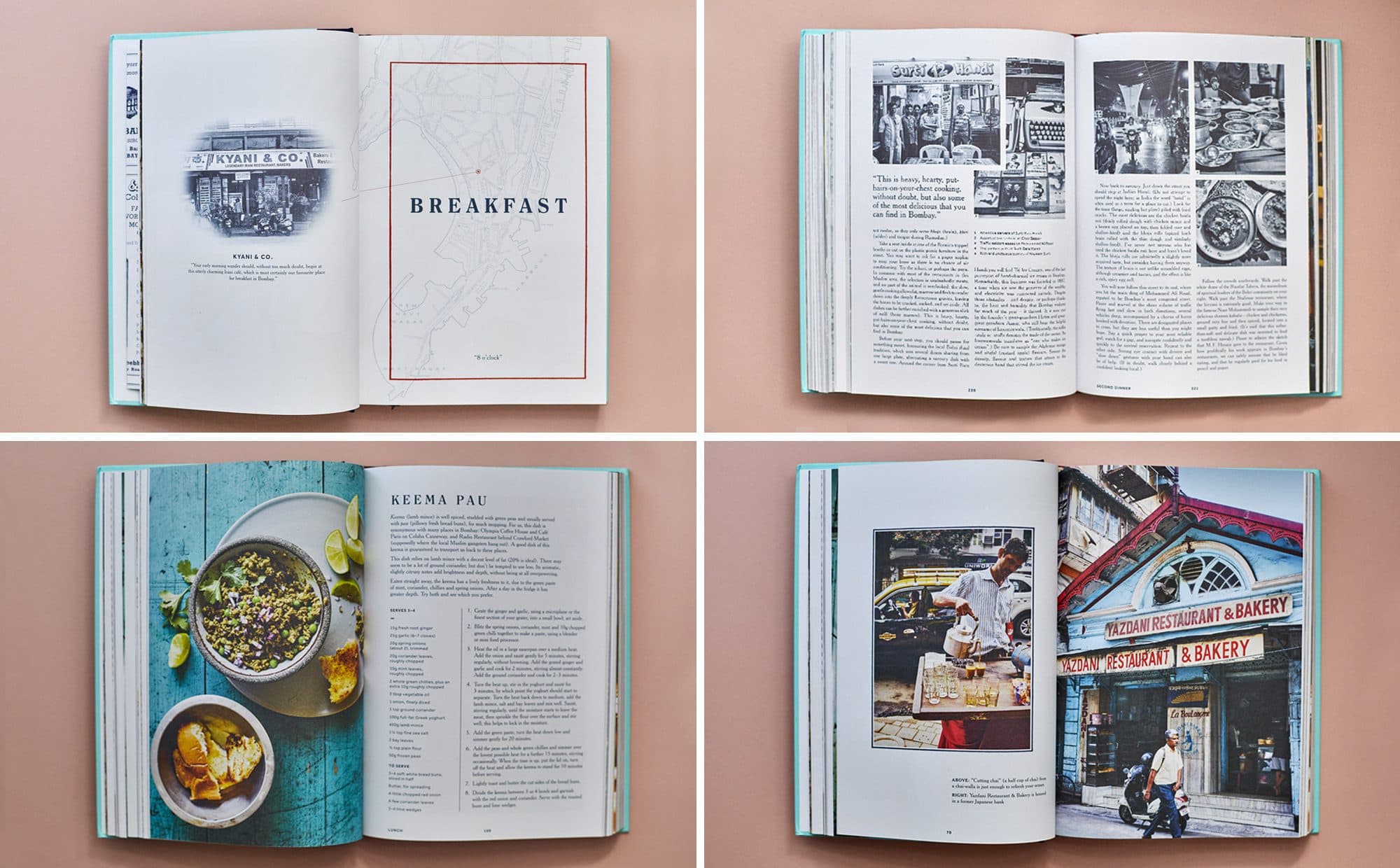

The book was designed by UK-based brand design agency APE and it appears to be every bit as beautiful and eccentric as the brand. This is no mere collection of recipes. Yes, there are over 100 recipes which will show you how to cook Dishoom meals, but they’re organized like a “a travelogue of sorts for those who dream of escape.”

At some point, you must ask: should this cultural artefact be described as a cookbook? While its origins are rooted in that typology, Dishoom: From Bombay with Love feels like something that aspires to something completely, wonderfully different.

You can get Dishoom: From Bombay with Love directly from the Dishoom website, or from Amazon.

Eleven Madison Park

I discovered Eleven Madison Park in the same thread where Andy mentioned The French Laundry, Per Se.

Here again, I was thrilled to learn that the cookbook contained essays. The added revelation was how deeply personal the essays could be. Andy shared this borderline disturbing snippet.

“Lovers fell asleep waiting for me to return home at night … I did not have time to read bedtime stories to my children … I am divorced … I still hurt … A dish ilke this is drawn from the long hours and years in the kitchen … There are no steps to skip.” Remarkable. pic.twitter.com/RgsXiYhsaX

— Andy Matuschak (@andy_matuschak) October 29, 2020

This stunned me.

I had no idea cookbooks could be like this.

You can get Eleven Madison Park from Amazon.

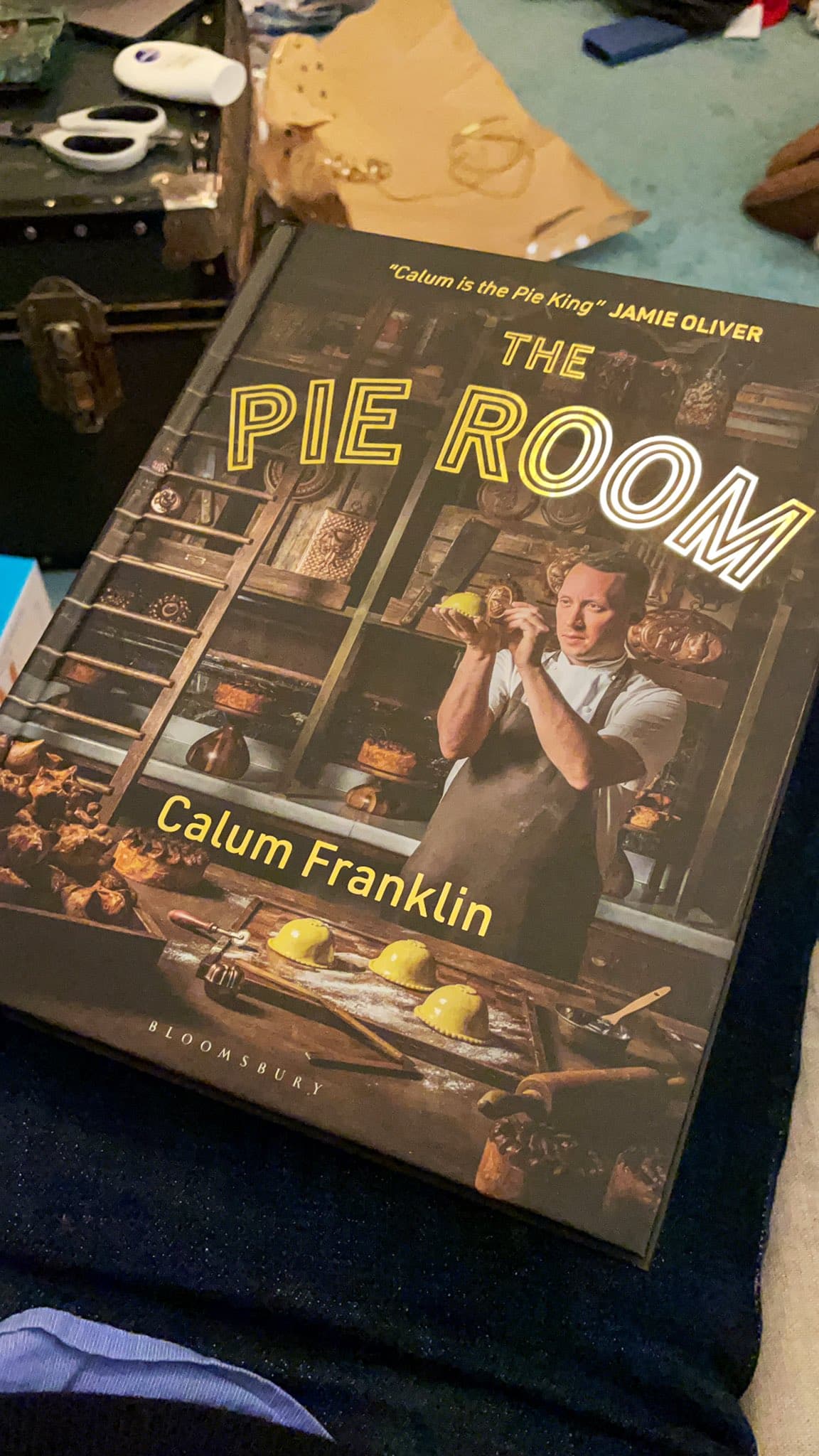

The Pie Room

Calum Franklin’s The Pie Room is the very first cookbook I read from end to end. I discovered it via this tweet by Tom Coates.

Got this extraordinarily British book for Christmas and it is *amazing* and I want to cook 2/3rds of the things in it, particularly the insane pie with three great chunks of bone sticking out. pic.twitter.com/Kxv3ExYbJ4

— Tom Coates (@tomcoates) December 26, 2020

I am OBSESSED with these photographs!

As in, I genuinely had NO IDEA that pies could come in these shapes and forms!

This cookbook made me aware of types of food I didn’t know existed, and I love it for that reason.

I found myself thinking a lot about The Pie Room while reading The French Laundry, Per Se, for reasons I can’t fully articulate to myself. Part of it might be because, reading one right after the other, I couldn’t help noticing similarities and difference between Chef Keller and Chef Franklin. Both share a a ravenous curiosity about ingredients and technique, obsess about how the design of their workspace directly contribute to work, and take every opportunity to talk about their team.

But there is a wink and a smile that runs beneath Franklin’s writing, which makes it read like good-natured gossip. He’s clearly very serious about his work, but I would never excepted a cookbook could be funny, and yet, I found myself laughing out loud at Franklin’s wry, disarming humour in places. I’m glad I read The Pie Room first - it’s such a joyous, accessible introduction to cookbooks, and it lit the fuse that made me curious to read others.

You can get The Pie Room from Amazon.

What is a cookbook?

So, those were the cookbooks that got my attention in 2020.

When I think about why these four books, specifically, resonated with me, I think the thing they all have in common is that they taught me something new. There are thousand of cookbooks out there, but these four expanded and deepened my understanding of what this specific typology of books could be. To the point where I frequently found myself wondering whether we needed a new name for this kind of cultural artefact?

To call something a cookbook is to signal to a certain audience that it is mostly a bundle of recipes, and little more, but I believe this misunderstanding limits the possible audience for these remarkable texts.

I am thankful to have been corrected, and doubly thankful for their lessons.

If you have any recommendations for other cookbooks that have this quality, please share them with me on Twitter.