Favourite fictional characters of 2020

Who, if I hadn’t met them in media in 2020, would my life have been poorer for it?

Sheltering in place for weeks at a time, I found escape in several books and TV shows. It’s possible that I consumed more popular culture in 2020 than the previous several years combined.

Some of the characters I met during those adventures struck me in ways that I’ll carry with me for a long time.

This list answers the question “Who, if I hadn’t met them in media in 2020, would my life have been poorer for it?”

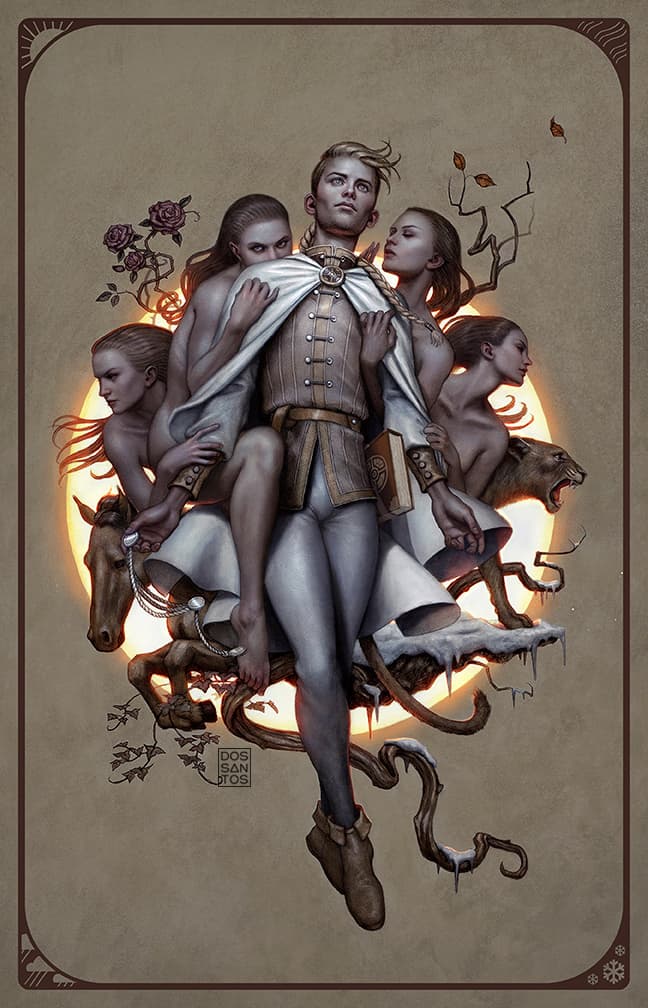

Ista dy Chalion (Paladin of Souls)

Paladin of Souls is a medieval fantasy novel by Lois McMaster Bujold.

This novel - about a cursed woman who saves herself by saving others - tells us that we can be redeemed, that we are worth saving. That we can begin again, and that we’re never too old or too far gone to take new shapes.

Ista embodies this idea completely. When we meet her, she has been many things: a daughter, a mother, a queen, a widow, a pawn of gods - even a murderess. She’s always been defined in relation to other people, and now, middle-aged and spent, she finds herself adrift. She asks “Who am I, when I am not surrounded by the walls of my life?”

Over the course of many trials, she learns that she has more agency to answer this question than she had ever imagined.

Ista is easily my top fictional character of 2020.

I love her raw intelligence. Often, when authors attempt to signal that a character is smart, they beat the point over the head by making them achieve some impossible feat of deduction. Bujold never reaches for this crutch with Ista. Instead, she communicates Ista’s supple mind in her measured assessment of people and her ability to unarm anyone with a deft phrase.

I love Ista’s strength. She has been through hell, but instead of letting the blows warp her spirit, she has let it temper her into something remarkable that allows her to protect others. She is definitely not superhuman. She hurts. She despairs. But she endures and persists, despite it all. I envy her poise, her steel, and her dignity, brittle though it may be.

I love Ista’s sense of humour. When the book begins, we only see weak embers of this, but as the story progresses, her wry amusement becomes a comforting vein of warmth running beneath her carefully cool exterior. It’s a pleasure to watch her blossom over time as she returns to herself.

And above all, I love Ista’s deep wells of grace.

Ista has had so much taken from her, and yet she is a constant solace to others. Often, she must give tough love, but it is love all the same, and she is a brook of blessings wherever she finds herself.

Near the end of the book, she speaks with a broken man, only recently re-united with the remnants of a soul quite literally gnawed on by demons.

Before he was captured, he had lived wickedly. Ista tells him:

“…your soul is your own, now, to make of what you will. We are all of us, every one, our own works; we present our souls to our Patrons at the ends of our lives as an artisan presents the works of his hands.”

“I am too marred,” he sobs.

“You are unfinished. They are discerning Patrons, but not, I think, impossible to please. The Bastard said to me, from His own lips that the gods did not desire flawless souls, but great ones. I think that very darkness is where the greatness grows from, as flowers from the soil. I am not sure, in fact, if greatness can bloom without it … do not despair of yourself, for I think the gods have not.”

“I am too old to start over.”

“You have more years ahead of you now than Pejar, half your age, whom we buried outside these walls these two days past. Stand before his grave and use your gift of breath to complain of your limited time. If you dare.”

He jerked a little at the steel in her voice.

“I offer you an honorable new beginning. I do not guarantee its ending. Attempts fail, but not as certainly as tasks never attempted.” He vented a long exhalation. “Then … that being so, and knowing what you know of me—which is, I think, more than ever I confessed to anyone, living or dead—I am your man if you will have me, Royina.”

Ista tells us we are worth saving. We believe her because we know the story of her redemption.

I am thankful to have met her.

Deku (My Hero Academia)

In the world of the anime My Hero Academia, superheroes are a trade just like any other. Izuku Midoriya (nicknamed Deku) is a student at a highly respected hero academy trade school and the protagonist of the show.

Deku is a idiot.

He is idealistic to a fault. He throws himself in harm’s way to help others with no sense of his own safety. He, quite literally, destroys parts of his body every time he uses his powers, and he does so again and again and again and again and again and again till his arms have the flesh nearly stripped from bone.

He puts others first in the most maddening, most unrealistic ways. His sense of pride comes solely from his ability to serve his people. He has the power of a near god and carries himself like a servant. He is completely without ego.

He is a fool.

He is the best of us.

I wept several times.

The Bastard (Paladin of Souls)

The Bastard is one of the five gods in Lois McMaster Bujold’s World of the Five Gods, and Ista’s patron deity.

He is a trickster / jester figure in a way that is familiar in other common myths (think Loki, Anansi, Wit from Brandon Sanderson’s Cosmere, etc).

The Bastard is named, or makes an appearance, in all of the three novels and nine novellas that make up the series, but I enjoyed him best in Paladin of Souls.

I love how Bujold takes the concept of the jester god figure in mythology and pushes it into new territory. This is a god who is feared and respected, yes, but you’ll find the disciples who love him best will openly roll their eyes at his dramatics. When he shows up in person in the books, it’s usually to get yelled at to his face. It’s hilarious.

As an example, this a conversation between a saint of The Bastard and a character who is unlucky enough to have received the gods’ attention (from The Hallowed Hunt).

Lewko sat back, breathing out through pursed lips.

“Was it your god, in the bear? Do you think?” Ingrey prodded.

“Oh”—Lewko waved his hands—“to be sure. Signs of the Bastard’s holy presence tend to be unmistakable, to those who know Him. The screaming, the altercations, the people running in circles—all that was lacking was something bursting into flame, and I was not entirely sure for a moment you weren’t going to provide that, as well.” He added consolingly, “The acolyte’s scorches should heal in a few days, though. He does not dare complain of his punishment.”

There is something fundamentally queer about The Bastard, not least because in the books he is quite literally the patron god of homosexuals. He is the “god of things out of season,” simultaneously the weakest of his family of deities, but the one most comfortable in the place between planes. This is how he is described in The Curse of Chalion, the prequel to Paladin of Souls.

[Umegat] held out his hand, thumb up, and waggled it gently from side to side. “The Bastard, though the weakest of His family, is the god of balance. The opposition that gives the hand its clever grip. It is said that if ever one god subsumes all the others, truth will become single, and simple, and perfect, and the world will end in a burst of light. Some tidy-minded men actually find this idea attractive. Personally, I find it a horror, but then I always did have low tastes. In the meantime, the Bastard, unfixed in any season, circles to preserve us all.” Umegat’s fingers tapped one by one, Daughter-Mother-Son-Father, against the ball of his thumb.

He is fundamentally in-between, with an almost childlike delight in the absurdity of the world, and within the pantheon, he is seemingly the one who cares most about small people, and low things. He is the lord of hell, and the first to laugh out loud at crude humour.

Above all, I love the Bastard as mediator.

He intercedes.

This is the flavour of prayer he receives (from Penric’s Mission).

Pen considered this. For a long time. Then whispered, “Lord Bastard, Fifth and White,” and faltered. He held up his hands in the black, fingers spread wide in supplication. “Master of all disasters out of season.” Indeed. “I lay this day as an offering upon your altar. If it please you, take it from me.”

I think the following passage is when I fell in love with Him.

Dy Cabon returned to ritual and called down the fivefold benison, asking of each god the proper gifts, leading the respondents in praise in return. Of the Daughter, growth and learning and love; of the Mother, children, health, and healing; of the Son, good comradeship, hunting, and harvest; of the Father, children, justice, and an easy death in its due time.

“And the Bastard grant us …”—dy Cabon’s voice, fallen into the soothing singsong of ceremony, stumbled for the first time, slowing—“in our direst need, the smallest gifts: the nail of the horseshoe, the pin of the axle, the feather at the pivot point, the pebble at the mountain’s peak, the kiss in despair, the one right word. In darkness, understanding.” He blinked, looking startled.

“In our direst need, the smallest gifts…the one right word.”

In a year of almost biblical reckoning, I found myself understanding the urge to prayer probably for the first time in my entire life.

In Bujold’s Bastard, I found solace in the idea that there might be someone listening.

Clancy and Clancy’s Mom (The Midnight Gospel)

S1E8 of @MidnightGospel is a complete devastation. A complete triumph. Undone.

— Emmanuel Quartey (@equartey) May 10, 2020

The Midnight Gospel is an animated show on Netflix about a boy named Clancy and his adventures.

The audio in the show comes from real life interviews from comedian Duncan Trussell’s podcast, The Duncan Trussell Family Hour.

The eighth episode of season 1 features a recording of a conversation between Duncan and his mother, three weeks before she died from cancer.

you cry. pic.twitter.com/vNazgARzVN

— The Midnight Gospel (@MidnightGospel) May 2, 2020

Candidly, I am not yet able to have a stable conversation about this episode and what it tells us.

Bless this show.

More about Deneen Fendig, Duncan/Clancy’s mom.

Sunspark (The Door into Fire)

The Door into Fire is a fantasy novel written and published over forty years ago by Diane Duane.

The book tells us to not let the world make us hard.

That it is worth it to strive mightily even in the face of overwhelming odds. That the pursuit of joy and love - gifting it and receiving it - requires no justification. And that everything ends, and while it is inevitable, we can tip the scales to make it a good life for each other.

Sunspark is a fire elemental in the form of a great flaming horse who is slowly learning to understand humans. But Sunspark is still so far from this understanding that everything that comes out of its mouth is both hilarious and alarming, such as when it jokes good-naturedly about killing people, because it assumes people just “come back” like elementals do.

While Sunspark is usually used as comedic relief for much of the novel, the character comes to embody the principle of learning to change, and learning to be vulnerable for others.

Sunspark had become unique.

Sunspark was changing. Daring to change. Trying to change.

It had managed to conceive of something totally outside of its needs. It had come to understand love, and it was daring to experience it, flying with doomed valor into the face of something that could only cause it infinite pain. But daring it nonetheless, for the sake of the dare, for the possibility of learning something new, of becoming something it had never been or known. Reaching out into the darkness outside of itself, as Herewiss had turned himself outward and sought to grow into the Universe.

None of its kind had ever dared so. It knew as much, and trembled with fear even as it bent over Herewiss’s stiff body and feared for him, loved him. It broke the laws that the Universe had set up for its kind; and it knew what it did, and it feared—but it loved—

Sunspark faced Herewiss, and perceived him.

Sunspark ultimately makes a momentous decision that turns the tide and saves its loved.

“Sunspark, what you did last night—”

(I would do again,) it said. (You are my loved. And anyway, shall I dare less than you?)

Herewiss put his arms around Sunspark’s neck again, gathered it close, and wept like a child.

“You are my loved. Shall I dare less than you?” probably best summarizes the politics of Door into Fire, which is that: loving is risk, and its reward, while sometimes bitter, can also be very, very sweet.

Penric and Desdemona (The Penric & Desdemona Series)

These characters are yet again from Lois McMaster Bujold’s World of the Five God’s universe. Over nine novellas (and counting), we follow the adventures of the sorcerer Penric, and the demon from which he draws his power, Desdemona.

I love this pair.

I think it’s the first example I’ve encountered in fiction of a long, sustained, healthy relationship between a young man and an older woman. Desdemona is, of course, not human, but the previous 10 people with whom she bonded had mostly been relatively older women, so that’s how she reads in the book.

The novellas featuring this duo are relatively lighthearted compared to the novels. The stakes in their stories are always moderate, but even here, where the scale of the story is smaller, Bujold’s incredible writing makes the challenge hit just as acutely as any grand tale. Inevitably, the two save the day, and everyone lives happily ever after.

During the early days of the pandemic, I really appreciated these simple stories of good people doing the best they could, every day.

The stories almost read like parables, which tell us that wherever we find ourselves, we should work to increase dignity, and that we must carry ourselves in a way that allows us to be the answer to someone’s prayer.

Marcus Tibbs (Bloodshot)

Bloodshot is the 2020 film adaptation of the Valiant Comics superhero of the same name.

The film introduces a brand new character named Marcus Tibbs, a former sharpshooter in the US army who loses his sight in battle. With few options, he ends up with military contractor RST, which gives him sight-restoring ocular implants.

Tibbs, played by Alexander Hernandez, is a standout character. Hernandez steals every scene he’s in, despite having relatively few lines, and I found myself thinking about his character long after the movie was over.

The reason Tibbs is one of my favourite characters of 2020 is because watching him, I found myself marvelling at technology in a way I hadn’t in a very long time.

Working in tech like I do, it’s easy to lose the sense of wonder at what technology lets us accomplish, but the character takes a relatively simple prompt - technology aided sight - and takes it so some pretty awesome places.

My very favourite scene is a chase scene where Tibbs and his partner go in pursuit of the protagonist. Tibbs steps onto a beautiful black motorcycle, dons a headpiece that looks more like armour than a bike helmet, and launches drones in the sky that give him 360 vision. This snippet of the movie is from that very moment.

The whole thing is just plain cool. Seeing Tibbs race through the city aided by his literal god’s-eye-view is probably the most seamless example of the relationship between man and machine I’ve seen in a long time. I loved seeing how technology expanded his span of influence and control, exponentially.

I really don’t know why, but this has really stayed with me. To be clear, one explicit narrative thread that runs through the movie is the high cost of the technology that pervades our lives, but for some reason, I also sensed a subtext that offered an alternate, more hopeful vision of how technology could better aid us.

I suspect that at least part of this reading has to do with Hernandez’s performance. He brings a depth of feeling and human warmth to the character that radiates off the screen. He took what would otherwise have been a one-note character and delivered a nuanced portryal of a conflicted man, trapped in a complicated situation.

I would honestly watch an entire movie focused just on Hernandez’s vision for Marcus Tibbs, and I sincerely wish he had played a larger role in the movie.

2020: A year of heroes

These were the characters I met for the first time in 2020, who, if I hadn’t encountered them, I believe that my life would be poorer for it.

When I ask myself what is common to all of them, I think what they share is that in one way or another, they give someone permission to be brave.

They advocate. They intercede. They create space. They hold space.

They bear witness.

They are, in someone’s direst need, “…the smallest gifts…the one right word.”